Welcome to the next battle of Gettysburg. What should be the appearance and purpose of this and any other National Military Park? As part of the Cyclorama parking lot deconstruction there will be a structure placed along the Taneytown Road. It is the old gateway for the road that connected the Emmitsburg Road (Steinwehr Avenue) and the Taneytown Road. The National Park Service includes the gate as item 74 in its Defense of Cemetery Hill Cultural Landscape Report: “This imposing and ornamental stone gateway was erected in 1923. The gateway was proposed by Colonel John P. Nicholson and designed by E. B. Cope in 1922 as a finishing touch for the national military park. Charles Kappes erected the foundations for the gateway entrance but the employees of the Commission undertook the remainder of the construction. The stone for the gateway was of native granite and was taken from Little Round Top. The Bureau Brothers foundry of Philadelphia cast the two bronze eagles, two bronze U.S. seals, and two tablets inscribed ‘Gettysburg National Military Park’ which graced the two central gate pillars. NPS disassembled this gateway during construction of the Cyclorama Center complex and the relocation of the Hancock Avenue entrance at Taneytown Road. The two bronze eagles were loaned to a local antiques dealer in the late 1960s and have since disappeared. The national seals and the gate tablets are in park storage. The … foundations for the gateposts and for the wing walls still exist, retaining the site and footprint of the gateway.” This view was taken facing northwest circa the early 1900s.

This aerial view shows the area of the old Cyclorama parking lot, and what is now the current National Cemetery parking lot. The parking area will be significantly reduced during this current restoration. The red star is the spot on which the Hancock Avenue Gate was located. This image is courtesy of googlemaps.

Originally, the road had a wooden gate… This view was taken facing west circa the late 1880s and shows the “Entrance to Hancock Avenue from Taneytown Road with wooden gate.”

…Which was then replaced by fencing from Lafayette Square. This photo shows the “Entrance to Hancock Avenue from Taneytown Road with Lafayette Square fencing.” This view was taken facing west in 1896.

In one of their recent blog posts the National Park Service was asked about why the Hancock Avenue Gate was being reconstructed. The park described the gate as a “commemorative feature” whose restoration was part of their “Commemorative Era Treatment Philosophy.” This image was taken from the the blog of the Gettysburg National Military Park, “From the Fields of Gettysburg.”

Commemorative Landscape restoration, or restoration of the park to what it looked like in the late 1800s and early 1900s was an option presented as part of the Gettysburg National Military Park General Management plan in the late 1990s. This image is courtesy of books.google.com.

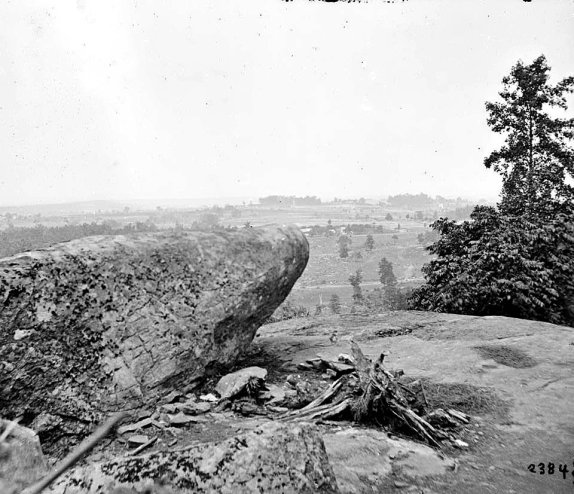

In 1999 the National Park Service chose to concentrate on restoring the battlefield closer to its 1863 appearance so that visitors would better understand how and why the battle was fought. This view was taken facing north towards Cemetery Hill from Little Round Top, circa July 15, 1863, by Mathew Brady.

However, in the adopted General Management Plan, the National Park Service did include some commemorative features from the 1880s-1920s to be added to the 1863 landscape. The Sickles “Witness Fence,” which separates the National Cemetery from Evergreen Cemetery, is an example of of a commemorative feature. The proposed plan (Alternative C) calls for this fence to be replaced with War Department era pipe and rail fencing. This view was taken from the southwest facing northeast at approximately 4:30 PM on Tuesday, August 12, 2008.

On their blog, the Park Service compares the construction of the gate to the construction of monuments. According to the Park, monuments and other structures are commemorative. One of the pictures that they showed in their blog was the “First Shot Marker” along the Chambersburg Pike with “commemorative era fencing” surrounding the monument. In our opinion, “one of these things is not like the other…” This view was taken facing northwest circa 1900. This image is courtesy of the National Park Service.

Monuments are certainly commemorative. They honor the people who fought here. But they are much more than that. They are INTERPRETIVE and educational. They help to make the battlefield one of the world’s greatest outdoor classrooms. Here is the monument to the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment on Barlow’s Knoll. This view was taken facing northeast at approximately 4:00 PM on Thursday, May 12, 2016.

Lest we forget, and more than a few people seem to want to forget this, the National Military Parks were not only established to remember the sacrifice of the men and women who fought here – they were established for military study. This image shows the monument/marker to Wilkeson’s (later Bancroft’s) Battery G Fourth U.S. Artillery on Barlow’s Knoll. This view was taken facing northeast at approximately 4:00 PM on Thursday, May 12, 2016.

In our opinion, monuments are not an intrusion on the historic (1863) landscape, they are a welcome addition/layer to the landscape. For instance, monuments give one an idea of where units fought and/or were positioned during the 1863 battle. This image shows the position of the 149th New York Infantry Regiment on Culp’s Hill. This view was taken facing west at approximately 5:40 PM on Tuesday, April 15, 2008.

Monuments show us what direction the soldiers were facing during the battle in 1863. This image shows the North Carolina State Monument on Seminary Ridge on a foggy day. This view was taken facing north at approximately 6:15 AM on Sunday, May 4, 2008.

Monuments show, describe, and present what soldiers did in 1863, many times at or near the location of the monument. This image shows the bas relief on the monument to the 12th New Jersey Infantry Regiment on Cemetery Ridge. The 12th New Jersey fought Confederates around the Bliss Farm. This view was taken facing west at approximately 7:00 AM on Sunday, June 22, 2014.

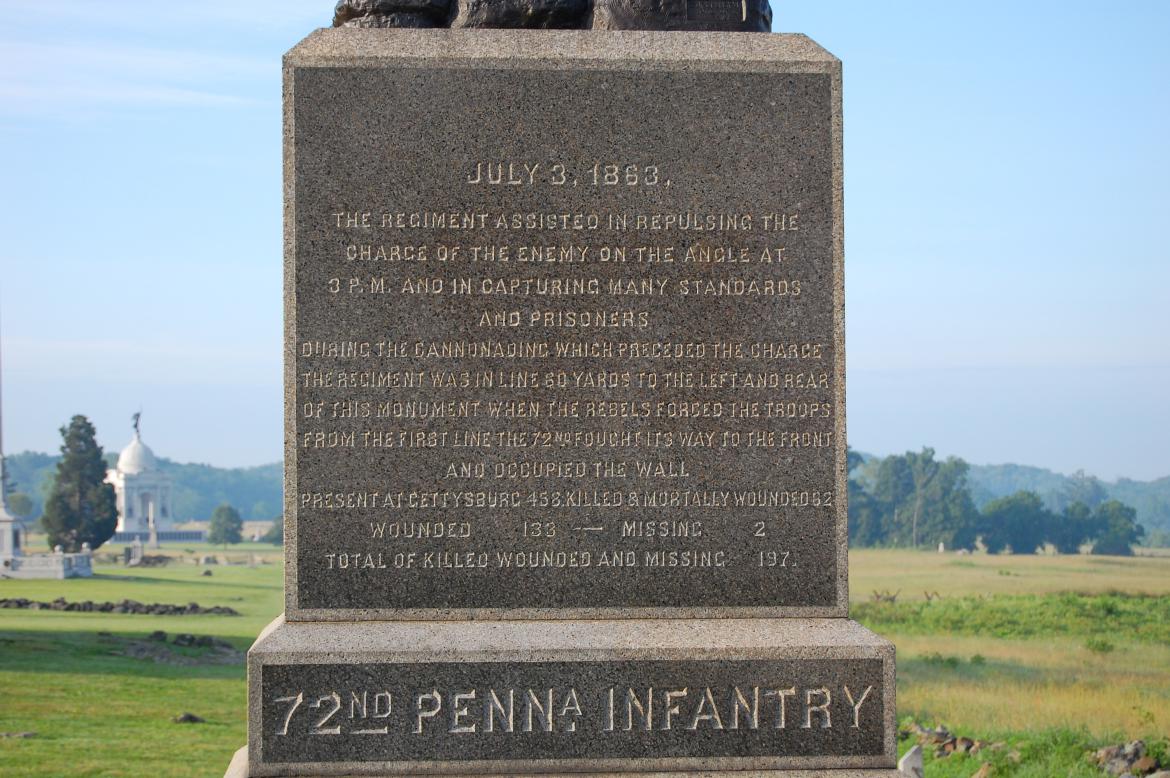

Monuments as an interpretive tool may tell us how many people were in a unit during the 1863 battle/campaign, and how many of those were casualties. This image shows a portion of the monument to the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment on Cemetery Ridge. This view was taken facing south at approximately 7:00 AM on Sunday June 22, 2014.

The War Department commemorative era pipe fences show where the Gettysburg Battlefield Association land and later the War Department land in the late 1880s-1920s was separated from private land. Period. They commemorate nothing. This photograph shows the monument to the 74th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment on Howard Avenue, which is part of the July 1, 1863 battlefield. This view was taken facing southeast circa 1900. This image is courtesy of the National Park Service.

Here is the 74th Pennsylvania Monument after the government acquired more land in the area and were assured that the playing fields of Gettysburg College would remain fields, as they were in 1863. The pipe fencing, which was at that point nothing more than an intrusion upon the historic 1863 landscape was removed. Do you really want the pipe fencing to return? If the battlefield is presented during the commemorative era, it should. This view was taken facing southeast at approximately 5:00 PM on Saturday, September 18, 2010.

Another link that the National Park Service attempted to make in their blog to justify why they wanted to put the Hancock Avenue gateway back is that stone walls on the battlefield are from the commemorative period because they were rebuilt during that time. We think that is a “reach.” Stone walls, while they may have been rebuilt in the late 1800s and again in the 1930s, for the most part mark farmers’ property lines at the time of the battle. They are an integral part of the historic 1863 landscape. This stone wall borders Wainwright Avenue at the bottom of East Cemetery Hill. The rider wooden fence on top of the stone wall gives them the nickname “pig tight and cow high.” Pigs can’t go through the bottom of the wall, and cows can’t jump over the top. This was view taken facing northeast at approximately 5:00 PM on Monday, April 25, 2016.

There are stone walls that were constructed by the soldiers during the battle. The stone wall shown here was constructed by Pennsylvania soldiers on July 3, 1863 in the area of the 20th Maine Monument on the south slope of Little Round Top. This view was taken facing southwest at approximately 8:00 AM on Sunday, April 17, 2011.

In our opinion, the Hancock Avenue Gate has no interpretive value, and little commemorative value. For instance, what does it commemorate? All it does is show an entrance to the park at a time when private land bordered the park and it was important to delineate government land from private land. The National Park Service now owns all of the land in this area, and the gate’s purpose is no longer needed. It and the wall in the background were not here during the battle. This will confuse most visitors as to the appearance of the battlefield during 1863. Let’s remember, visitors often ask guides if soldiers fought in and around the monuments. This view was taken facing southwest circa the early 1900s.

Also, the National Park Service claims that it doesn’t have enough money to restore much of the battlefield back to its 1863 appearance, such as getting rid of nonhistoric vegetation. Removing nonhistoric vegetation is specifically mentioned as a goal in the adopted General Management Plan. There are more than a few other projects that should have priority over this “project.” How does the National Park Service justify spending the time and money on the Hancock Avenue Gate and accompanying non historic walls that had nothing to do with the battle in 1863? How do they justify the cost, hours, and overall maintenance to keep up these structures over the coming years, decades, and centuries? This view was taken facing south on Culp’s Hill by Mathew Brady circa July 15, 1863.

The rehabilitation of Cemetery Ridge had us tear down the Cyclorama Building, because it was not an 1863 structure. Now we’re putting up another structure that wasn’t here during the battle only a few yards away. This view was taken facing southeast at approximately 4:30 PM on Sunday, February 24, 2008.

The National Park Service put a moratorium on any new monuments at Gettysburg in 1999. They felt that they “cluttered up” the battlefield too much and took away from its 1863 appearance. How does one justify not putting up any new monuments (which are interpretive) and putting this structure up which contributes nothing to understanding the battle? This view was taken facing southwest in the early 1900s. This image is courtesy of the National Park Service.

Next year the National Park Service is presenting their “Commemorative Era Treatment Philosophy” which will further justify adding structures to the battlefield that were part of the 1880s-1920s landscape. They will be inviting public comment. Here are the commemorative era gates on Wainwright Avenue. Do we want structures like this that were not here during the battle to be put up again? So the question is, do you want the battlefield to look as it did in the 1880s-1920s…. This view was taken facing north circa the late 1800s to early 1900s.

… or should a more focused effort be made to have the battlefield look as close as possible to its 1863 appearance? This image shows Mathew Brady and his assistants in Plum Run Valley looking towards the Round Tops in July, 1863. This view was taken facing southeast circa July 15, 1863. This image is courtesy of the National Park Service.