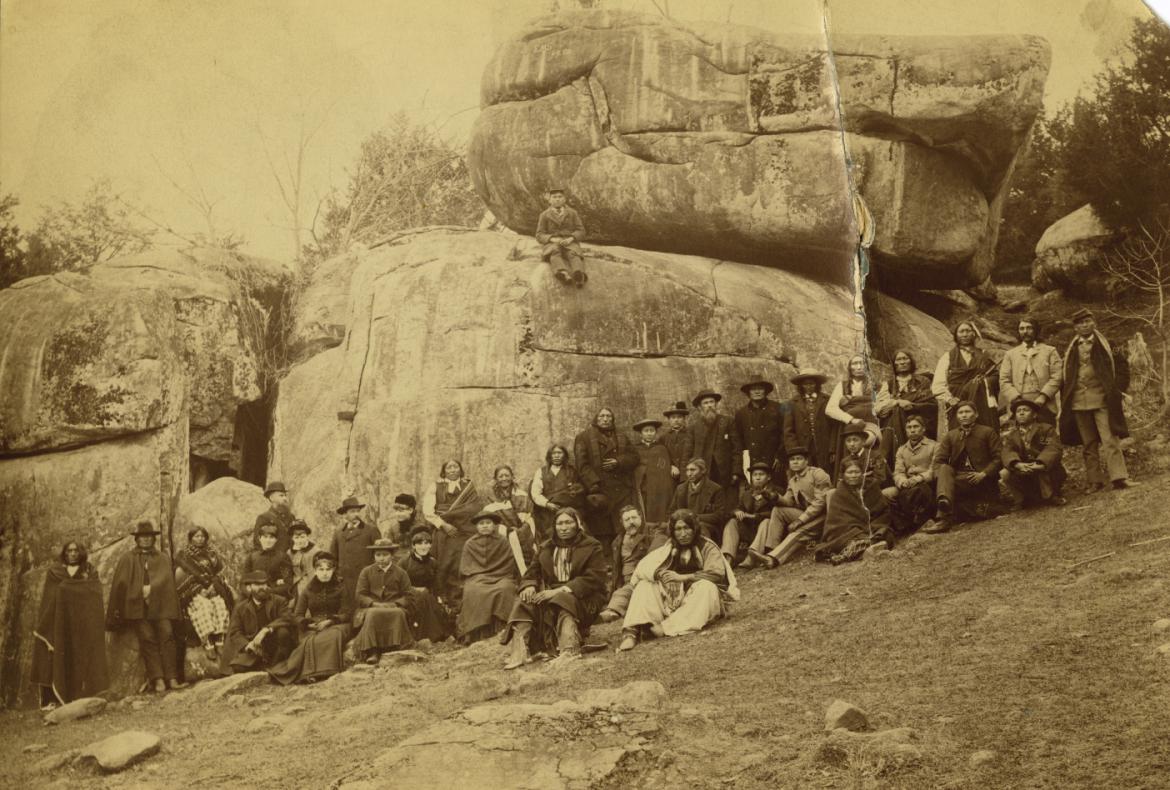

A group of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, as well as pupils and faculty from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This view was taken facing northwest at Devil’s Den on Friday, November 28, 1884, by William Tipton.

On Friday, November 28, 1884, a group of approximately fifteen Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, along with thirteen members of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, briefly toured Gettysburg. The delegation of American Indians were on their way to Washington, D.C., as well as visiting the Carlisle School.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians were historically located in the Great Plains, the land that currently ecompasses “Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan.” The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes formed alliances in the 18th and 19th centuries, splitting into distinctly Southern and Northern tribes. The Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho are among the individuals who visited here in 1884.

The 1880s were a continuation of many bad decades in the 19th century for the American Indian. The Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho had been granted reservation lands by the United States Government in present-day Oklahoma in 1865. By 1877 the last herds of buffalo had been killed, mostly by white settlers. This meant that by the early 1880s the Cheyenne and Arapaho people were forced to raise cattle. Grazing and leasing rights to cattle, as controlled by the Office of Indian Affairs (today’s Bureau of Indian Affairs) was part of the reason for this trip by members of the tribe. After their visit to the Carlisle School, they continued on to Washington, D.C., where they were present for the Senate Hearing for the Committee on Indian Affairs in December of 1884. The gentleman with the beard, seated in the center of this Tipton photograph, is William David Holtzworth, the group’s guide at Gettysburg, a veteran of the 87th PA Infantry, and the fourth Superintendent of the Soldiers National Cemetery.

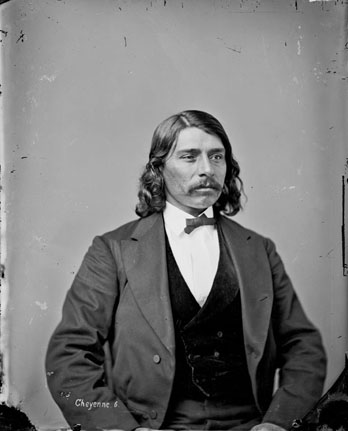

Most of the Indians making the journey across the country to the Carlisle School and Washington, D.C. did not speak English. They required an interpreter, and the man interpreting for this group was named Edmund Guerrier, who is pictured standing, second from the right (the light-colored suit).

Edmund Gasseau Choteau Le Guerrier was born to a French fur trader and a Cheyenne mother in 1840. Guerrier’s mother died of cholera in 1849. When his father died eight years later, Guerrier returned to the Cheyenne people. He is most well-known for bearing witness to the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864 and testifying about it in front of Congress in 1865. Almost 20 years to the day that this photograph at Devil’s Den was taken, on November 29, 1864, approximately 170 Cheyenne Indians (mostly women and children) were massacred by approximately 800 United States Cavalrymen under the command of Colonel John Chivington. Guerrier survived the massacre by fleeing five miles to the north when he realized what was happening. In retaliation for this massacre, many of the Cheyenne joined a group of Indians known as the “Dog Soldiers,” a group that continued on into the 1880s, and who were discussed at the Senate Committee hearing the week after this photo was taken.

After the Sand Creek Massacre, Guerrier elected to work for the Department of the Interior, who had taken control of the Office of Indian Affairs from the War Department in 1849. Guerrier worked as an interpreter, as well as informing on Indian raiding parties and assisting Winfield Scott Hancock’s 1867 expedition in the Cheyenne War. He performed interpretative duties for Cheyenne delegations to Washington D.C. in 1871, as well as in 1884 with this group of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. Guerrier married the daughter of another half-Cheyenne interpreter, George Bent. Bent was also present at the Carlisle School in November of 1884, but was unfit to make the trip with the delegation to Washington, D.C. and Gettysburg. He was later fired as an interpreter due to his alcoholism, but went on to write a series of detailed accounts of the Cheyenne people in his letters. Both Bent and Guerrier’s double life with the Cheyenne and their varied cooperation with the United States Government make them controversial figures in American Indian history. This view was taken circa the 1880s.

The white women pictured in this photograph are likely faculty members from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. In the 1880s the cry of the United States Government in regards to the American Indian was “Assimilate!” The infamous “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” was one of the guiding principals behind the creation of hundreds of boarding schools, both on reservations and in Carlisle, PA. The Carlisle School was the largest and most infamous of the boarding schools, operating until 1918.

At the time of this visit to Gettysburg in 1884, the Carlisle School had approximately 400 students, shown here in an unidentified month in the same year. Though boarding schools to assimilate Indians had begun as early as the 1860s, they were widely seen as a failures by the United States Government. The schools were run by Indians and this was seen as a reason for their “failure” to assimilate. In the 1880s the Office of Indian Affairs put their agents in charge of the schools.

In the course of its operation, hundreds of children died while at the school. In the Senate Hearing that took place in the week after Tipton’s Devil’s Den photograph, the Office of Indian Affairs agent in charge of the Cheyenne-Arapaho territory was asked, “Have any of the Cheyenne and Arapahoes been sent to Carlisle?” He explained that there were 54 Cheyenne and Arapaho children at Carlisle in 1884, though at least twenty had run away, and an additional dozen were sent back home. Dyer explained that they would go back to their old life and regretted that he could not “control them,” citing a “radical defect in the condition of the tribe” and asking to keep students at the school five years instead of three. The delegation from the Cheyenne-Arapaho that visited Gettysburg likely stopped in Carlisle first, where they then joined up with members and pupils of the school. This is a picture of the faculty of the Carlisle School, taken in July of 1884.

The group took the 8:30 AM train of the Gettysburg-Harrisburg Railroad from the Carlisle Branch, arriving in Gettysburg around 10:00 AM. After being taken around the battlefield by carriages and having their photograph taken at Devil’s Den by William Tipton, they had lunch at the Eagle Hotel. The Eagle Hotel was at first a two story building constructed in the early 1830s. The third story of the structure was added circa 1857. It functioned as a stop on the stage coach line from Chambersburg to Gettysburg. It was also used as a gathering place for the Republican party. The Democrats used the Globe Inn on York Street. A fire destroyed this building in 1894. It was replaced by larger versions of the hotel until a fire destroyed the last structure in 1960. A gas station was located here before the 7-Eleven convenience store that currently stands on this property today. This view was taken facing northeast circa 1888.

The Gettysburg Compiler reports that the Eagle Hotel register that afternoon “has the following names: Powder Face, Left Hand and Squaw, White Bear, One-Eye-Antelope, Big Jake, White Wind and Squaw, Old Crow, Cloud Chief, Red Wolf, Black Wolf and Squaw, Left Hand Squaw and Yellow Bear: with young Powder Faces, young Yellow Bears, Red Wolfs, and so on, the names of the latter written by themselves in fairly legible hands.” The delegation took the afternoon train back to Carlisle at 4:20 PM, arriving back in Carlisle around 6:00 PM. This view was taken facing northwest at Devil’s Den on Friday, November 28, 1884, by William Tipton.